SPRINT-MIND Sub-Study

SPRINT-MIND: THE BEST EVIDENCE TO DATE LINKING BLOOD PRESSURE AND COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

Kenneth Lam, MD FRCPC ABIM certified in Internal Medicine

Clinical Fellow, Division of Geriatrics, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto

Key highlights:

- SPRINT-MIND is a randomized controlled trial of intensive systolic blood pressure control to a target of under 120 mmHg and is the first major trial to demonstrate that an intervention reduces the incidence of mild cognitive impairment.

- The quality of evidence is limited because statistical significance was met on a secondary outcome but not the primary outcome of probable dementia.

- The result is gaining broader acceptance because of mechanistic plausibility: mild cognitive impairment precedes dementia and the trial was terminated early for benefit in cardiovascular events, potentially limiting the ability to observe the development of dementia.

- It offers further support for the hypothesis that hypertension causes dementia, but may not be practice-changing as intensive blood pressure control is already in guidelines due to cardiovascular and mortality benefit.

Dementia has multiple well-documented, potentially modifiable risk factors such as hearing loss, depression, and hypertension. However prior to this trial, no randomized controlled trials existed demonstrating that mitigation of hypertension resulted in fewer cases of mild cognitive impairment or dementia. The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial – Memory and Cognition in Decreased Hypertension (SPRINT-MIND) published this January is the first to do so, offering encouraging, yet indefinitive evidence that we can prevent or delay dementia1.

Methods

The SPRINT trial was a single-blind randomized controlled trial published in 2015 demonstrating that intensive systolic blood pressure management (target <120mmHg) versus standard management (target <140mmHg) reduced the risk of a composite outcome of myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure and cardiovascular death (1.65% per year vs. 2.19% per year, HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.64-0.89)2. It enrolled 9,361 adults over the age of 50 (mean age 67.9 years) with a systolic blood pressure between 130 and 180 mmHg and increased cardiovascular risk. Excluded patients were those with dementia, on dementia-modifying medications, prior stroke, diabetes mellitus, or residing in a nursing home, among other criteria.

SPRINT-MIND was a pre-planned sub-study of the SPRINT trial. To test the hypothesis that intensive blood pressure reduction in this cohort would reduce the primary outcome of probable all-cause dementia, they planned cognitive assessments alongside the main trial at baseline, every 2-years, and at study completion. Secondary outcomes were mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and a composite outcome of dementia or MCI.

Cognitive assessment at each follow-up consisted of a screening assessment (including tests of learning, memory, and processing speed), additional functional assessment if patients scored positive on the screening, and an extended neuropsychological battery if functional impairment was identified or if errors in delayed recall were noted. These data, along with information about the patient’s mood and health were used by two members of an adjudication panel to independently determine one of three possible outcomes: no impairment, MCI (if there was a decline in cognition from the patient’s baseline in at least one cognitive domain), or dementia (if there was cognitive decline and functional impairment). Disagreements were discussed by the full panel and decided by majority vote. A diagnosis of MCI required an adjudication decision of at least MCI on two successive visits.

SPRINT was terminated before the pre-planned average of 5 years due to early signs of benefit in the primary outcome of reduced cardiovascular events, after which point blood pressure medications were no longer supplied by the trial and care was returned to primary care physicians. This prompted investigators to extend follow-up with one additional visit after study completion.

Results

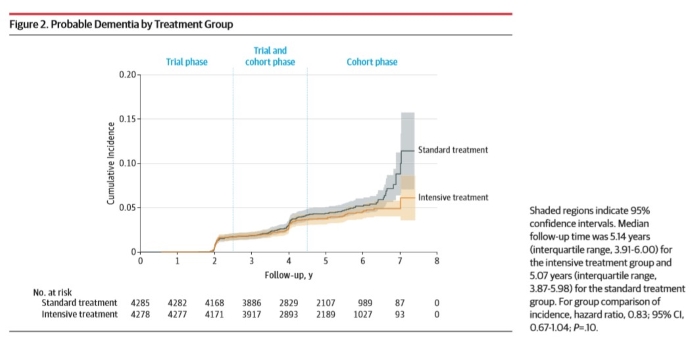

Although there was no statistically significant reduction in probable dementia (7.2 vs 8.6 cases per 1000 person-years, HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.67-1.04), the authors did find a statistically significant reduction in their secondary outcome of MCI (14.6 vs 18.3 cases per 1000 person-years, HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.69-0.95) and in the composite outcome of MCI or dementia (20.2 vs 24.1 cases per 1000 person-years, HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.74-0.97). The median intervention period was 3.34 years and median follow-up period was 5.11 years. During the intervention period, the mean between-group difference in blood pressure was 13.3 mmHg, but at extended follow-up, the between-group difference fell to 6.4mmHg. Completion rates of cognitive assessment were also greater than 90% at pre-planned visits but fell to 60% during extended follow-up. Risks of treatment included hypotension (HR 1.67), syncope (HR 1.33), electrolyte abnormalities (HR 1.35) and acute kidney injury (HR 1.66).

Cautions

Commentaries have highlighted that a lower-than-expected incidence of dementia and early termination of the trial contributed to the failure to demonstrate significance on the primary outcome3,4. Without a positive primary outcome, it is premature to definitively state that intensive blood pressure management prevents dementia, but results remain encouraging because of mechanistic plausibility and the absence of higher-quality evidence. It seems there was less MCI in the intervention group, and since MCI often precedes dementia, SPRINT-MIND may have simply followed patients for too short a time to observe the development of dementia5. Blood pressure control in the intervention group was also less intense once the trial was terminated, further attenuating the expected effect. As a result, the Alzheimer’s Society has funded an extension of this trial (SPRINT-MIND 2.0) to continue exploring links between hypertension control and dementia prevention6.

The mean age of trial participants was 67.9 years, limiting the generalizability of results to older patients.

Other data from SPRINT-MIND are awaiting publication. In their protocol, 2,800 patients were planned to receive more comprehensive cognitive assessments at each follow-up visit. Published results from their neuropsychological batteries will help place the results of SPRINT-MIND in the context of other randomized controlled trials that have observed domain-specific improvements with other interventions such as cognitive training and multidomain interventions7,8. A smaller subset of 640 proposed patients received MRIs, and those results will help support the hypothesis that dementia from hypertension is mediated by small vessel ischemic disease.

Implications

The study is major progress in our scientific understanding of dementia prevention, offering strong support that hypertension causes it and is something we can intervene upon. It is less clear if SPRINT-MIND will be practice-changing, as the cardiovascular and mortality benefits of intensive blood pressure control demonstrated by the parent study SPRINT is already making its way into guidelines9.

For further reading:

- The SPRINT MIND Investigators for the SPRINT Research Group, Williamson JD, Pajewski NM, et al. Effect of Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control on Probable Dementia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321(6):553. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.21442

- The SPRINT Research Group. A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(22):2103-2116. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511939

- Mayor S. Intensive BP control reduces mild cognitive impairment but not dementia, study finds. BMJ. January 2019:l425. doi:10.1136/bmj.l425

- Yaffe K. Prevention of Cognitive Impairment With Intensive Systolic Blood Pressure Control. JAMA. 2019;321(6):548. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.0008

- Ioannidis JPA. The Importance of Predefined Rules and Prespecified Statistical Analyses: Do Not Abandon Significance. JAMA. April 2019. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.4582

- Alzheimer’s Association Funds 2-Year Extension of SPRINT MIND Study. Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia. https://alz.org/news/2019/alzheimer-s-association-funds-two-year-extension-o. Accessed April 5, 2019.

- Belleville S, Hudon C, Bier N, et al. MEMO+: Efficacy, Durability and Effect of Cognitive Training and Psychosocial Intervention in Individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2018;66(4):655-663. doi:10.1111/jgs.15192

- Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A, et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2015;385(9984):2255-2263. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60461-5

- Nerenberg KA, Zarnke KB, Leung AA, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2018 Guidelines for Diagnosis, Risk Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment of Hypertension in Adults and Children. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2018;34(5):506-525. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2018.02.022

Kenneth Lam is a Clinical Fellow in the Division of Geriatrics, Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto, as well as Research Trainee at the Women’s College Research Institute. He will be starting a fellowship with the VA Quality Scholars Program in San Francisco in July 2019.

Kenneth Lam is a Clinical Fellow in the Division of Geriatrics, Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto, as well as Research Trainee at the Women’s College Research Institute. He will be starting a fellowship with the VA Quality Scholars Program in San Francisco in July 2019.

Excerpted as reprint from the IPA Bulletin, Volume 36, Number 2: IPA Members can download the full PDF issue here.