New MCI Guidelines & Cognitive "Growth Curves"

Assessing Cognition: New MCI Guidelines and Cognitive "Growth Curves"

Mark Rapoport, MD, FRCPC Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto, Associate Scientist and Geriatric Psychiatrist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Canada

Key highlights:

- New rigorously developed guidelines have been published on Mild Cognitive Impairment, including important suggestions on assessment and treatment, albeit with some concerns about applicability and involvement of clinician and other stakeholders.

- Researchers from Quebec, Canada have published a Cognitive Chart, analogous to growth charts in pediatrics (albeit in reverse), to standardize the Mini- Mental Status Examination (MMSE) scores by age and education, and to track progression over time.

There have been two recent publications of which IPA members should be aware, pertaining to cognition in older adulthood. One is an update of guidelines on assessment and treatment of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), and the second is a publication of an age -and education-standardized cognitive chart meant to track progression of cognitive difficulties over time.

MCI Guidelines.

The American Academy of Neurology published new guidelines on assessment and treatment of MCI in January 2018, updating an earlier 2001 guideline. A rigorous process was undertaken by the authors, who conducted a systematic review of the evidence across many topics pertaining to MCI. This included a Delphi process of ascertaining level of agreement with the strength of the evidence and confidence in the guideline recommendations. The manuscript summarizing the guidelines includes links to the full guideline methodology and results, as well as a brief summary of the recommendations. The determination of confidence in the recommendations incorporated deliberations on the cost/benefit ratio, the importance of outcomes, variation in preferences, and feasibility. Conflicts of interest were declared and well mitigated.

The recommendations include:

- Considering MCI as a diagnosis when patients (or their close contacts) have subjective cognitive complaints, rather than assuming the concerns are related to normal aging

- Using validated assessment tools and assessment of functional impairment

- Ensuring that clinicians lacking experience refer such patients to specialists

- Counseling that no accepted biomarkers are currently available

- Weaning from medications that can contribute to cognitive impairment

- Counseling that there are no pharmacological treatments with symptomatic benefit

The guideline also includes a helpful meta-analysis of higher quality prevalence studies, with prevalence estimates ranging from 8.4% for those aged 65-69 years (95% CI 5.2-13.4%, I2=0) to 25.2% for those aged 80-84 years (95% CI 16.5-36.5%, I2=0), and other analyses/summaries of prognostic studies.

Applicability of some of the recommendations may be debated. For instance, recommended tools for diagnosing MCI and completing neuropsychological tests after positive screens were not specified. In addition, the efficacy of certain treatments may currently lack the evidence to support definitive guidelines. For example, the statement that “for patients diagnosed with MCI, clinicians may choose not to offer cholinesterase inhibitors” seems to be broadly worded, in order to permit such treatments despite the acknowledgement that such clinicians “must first discuss with patients that this is…not currently backed by empiric evidence”.

Although the guideline was endorsed by the Alzheimer’s Association, the details of engagement of clinician, policymaker and caregiver stakeholders are not outlined in the documents, posing some limitations to the applicability of these suggestions, as well as stakeholder involvement. Nonetheless, this is a high-quality set of guidelines, with rigorous development, clarity in its scope, purpose, presentation and transparency.

Cognitive Growth Curves.

More than three decades after its’ first description in the literature, investigators from Quebec, Canada took the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) to the next level. Bernier et al addressed the long-established association of the MMSE with age and education, a factor that has limited its uncorrected use a cognitive screen. They used a sample from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging that was studied longitudinally over 10 years, including the MMSE, physician examination, and case-conferences to build a model that took both age and education into account. The MMSE was used to distinguish between subjects with dementia and healthy controls. The authors then validated their model with an independent roughly comparable sample from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center’s Uniform Data Set.

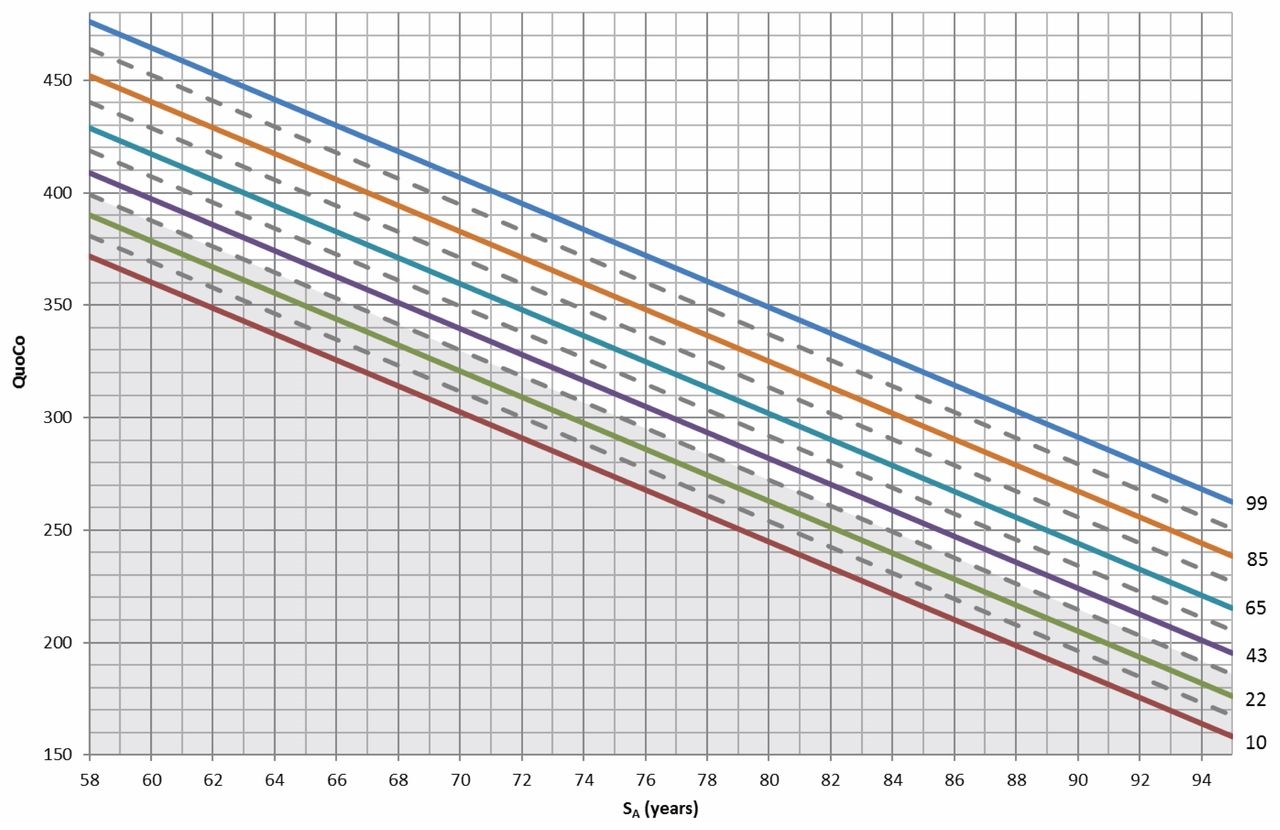

Based on their data, they suggest computing a “Cognitive Quotient” by dividing MMSE by age and multiplying this by 1000, and then calculating a “standardized age” using the formula age – 0.5 education. These computations are graphed on a “cognitive chart,” which looks similar to the “growth curves” used in pediatrics. The graph displays where the MMSE score (converted into the Cognitive Quotient) lies in percentile terms for that standardized age. When used over years, one would be able to notice clearly when a person’s cognitive performance on this simple screen (using relatively simple calculations) drops off of their trajectory.

The MMSE, of course, has its limitations as a cognitive screen, and work is ongoing to create similar cognitive charts for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). One implication of relying on the MMSE and these cognitive charts is that this is not an instrument sensitive to MCI. Another limitation of this work is that the diagnoses of dementia in both the original and validation samples incorporated MMSE scores, which may have inflated the observed sensitivities and specificities. Nonetheless, the idea of a cognitive growth chart that is analogous to growth charts in pediatrics (but in reverse) is an intriguing one, with practical value for clinicians and educators. A website and app (available on iTunes) provide detailed instructions and background for ready clinical implementation.

For further reading:

- Petersen, R.C., et al. Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment. Report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology 2018; 90(3): 126-135.

- Bernier, P.J. et al. Validation and diagnostic accuracy of predictive curves for age-associated longitudinal cognitive decline in older adults. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2017; 189 (48): e1472- 1480.

Dr. Mark Rapoport is a professor in the geriatric psychiatry division of the department of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, a clinical scientist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, and past President of the Canadian Academy of Geriatric Psychiatry. His main areas of research are traumatic brain injury in the elderly and the risk of motor vehicle collisions associated with neurological and psychiatric diseases and their treatments. After serving as an Assistant Editor, Dr. Rapoport became the Deputy Editor for the Research and Practice section of the IPA Bulletin in 2016. He regularly writes on recent advances in the field.

Dr. Mark Rapoport is a professor in the geriatric psychiatry division of the department of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, a clinical scientist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, and past President of the Canadian Academy of Geriatric Psychiatry. His main areas of research are traumatic brain injury in the elderly and the risk of motor vehicle collisions associated with neurological and psychiatric diseases and their treatments. After serving as an Assistant Editor, Dr. Rapoport became the Deputy Editor for the Research and Practice section of the IPA Bulletin in 2016. He regularly writes on recent advances in the field.

Excerpted from the IPA Bulletin, Volume 35, Number 1: IPA Members can download the full PDF issue here